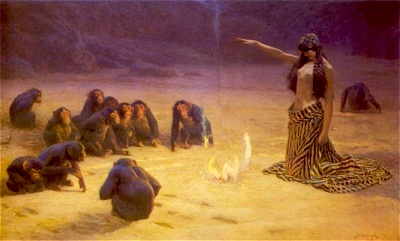

Heroic solitary security analysts, like Warren Buffett and Benjamin Graham are figures of the past — vestiges of forgotten times when capital markets were much, much simpler than today.

|

|

|

|

The solitary, heroic security analyst is long gone

|

|

|

|

|

Actually, Messrs Buffett and Graham moved away from classic securities analysis about two generations ago, as bond yields began to surpass stock yields and as control of most public corporations began to slip from individual shareholders and owner-managers, passing to mutual fund administrators and hired executives.

Mr. Buffett continued in finance in the holding company business (Berkshire Hathaway), while Professor Graham entered academia and life as a financial guru.

What changed since the time of Graham & Dodd?

Security analysts in the Buffett mold spent their days analyzing financial statements.

Most companies were relatively simple, with few subsidiaries and a single line of business.

|

|

|

|

A business an analyst could understand

|

|

|

|

|

One could tear into a financial statement, rip out some critical ratios (turnover of receivables and inventories, net working capital, return on equity, dividend payout, etc.) and then visit the company.

Touring the factory floor, chatting with workers on the assembly line, and having lunch with the sales manager, a good analyst could ascertain whether the balance sheet appeared to reflect reality, while gaining an insight into the future of the venture. With a little commonsense and willingness to go against the crowd, the solitary hero financial analyst could do quite well.

This was before the days of off-balance sheet financing, outsourcing of production to distant lands, just-in-time inventories and supply-chain management, and the subordination of individual companies to extremely complicated groups of interlocking financial interests.

Why financial statements have become less relevant

Although the SEC and the US Congress have not yet caught on, the organization of modern economic endeavors has far out-stripped the ability of accountants to present easily comprehensible financial statements that provide sufficient information to understand the strengths and weaknesses of a particular security.

The following diagram, is a vast simplification of the actual structure of many major international corporations traded on world stock exchanges today.

|

|

|

|

Economic groups easily confound modern accounting

|

|

|

|

|

It shows how willy-nilly interlocking relationships, often ultimately circular in nature, based on equity holdings, service contracts, off-balance sheet agreements, and memoranda of understanding, transcending international boundaries, with legal ties passing through non-disclosing offshore financial centers, can easily turn the financial statement of a single unit in the network (say the green box), into an irrelevancy.

A chart showing the myriad contractual and ownership relationships of a major international institution, like Citicorp, would likely cover an entire football field in a spider-web carpet of infinitely complex ownership and contractual relationships that defy attempts of accountants to present a “consolidated” statement of what, in essence, is beyond the capabilities of dual entry bookkeeping.

A decade ago, when I was advising securities regulators in Southeast Asia, my clients would come to me with charts far more complicated than the diagram above, with questions like, “Is Mr. A an affiliated person of Mr. B”, or “If Mrs C gives information about company X to Mr. D, is this insider information?” The answers were never obvious. Complexity can quickly trump the best regulation intended to protect investors.

The criticality of non-accounting information

Although, in the wake of a financial catastrophe, like the failure of Enron, Worldcom, the Crash of 2008, or the Madoff Ponzi scheme, the US Congress likes to call for tighter accounting standards or more effective oversight by market regulators, the truth is that those inclined towards bad behavior in securities markets can dream up complex schemes faster than regulators can write rules.

|

|

|

|

Complexity of design may amount to deception

|

|

|

|

|

Until a law is passed banning complex financial arrangements or requiring approval for new products and financial operations — as is done in the pharmaceutical industry — accounting information will become ever less central to the task of analysis of investment opportunities.

- Auction rate securities: Analysts at Standard & Poor’s gave most issues of auction rate bonds investment grade ratings because they were asking the wrong question, “What is the risk of default of this bond?”. The better question would have been, “What is the risk that this bond will become illiquid?”, but the analysts were not being paid to answer that question and investors lost billions.

- Behavior of investment management: Billions of dollars were lost in the Ponzi scheme because neither the SEC nor advisors channeling client funds to Bernard Madoff asked the simple question, “Is it reasonable for one man to have sole custody and discretion over billions of dollars of other people’s money, with the oversight of only a tiny auditing firm operating out of a store front in a New York suburb?”

- Rogue operations: The failure of Barings Bank a decade ago and the crisis at AIG following the Market Crash of 2008, both illustrate the fact that in large complex organization, a rogue operator or unit, a tiny part of the whole, can put an entire huge organization at risk. Details that escape the auditor, like a break-down in internal controls in a far off banking unit in Singapore, or unclear, non-standard terms of over-the-counter derivative contracts, not mentioned in the annual report to shareholders, can be instrumental is collapsing a giant financial institution.

Rethinking the analyst’s job

The old-fashioned, heroic security analyst, working alone in a dark room with a stack of annual reports, in a snow-bound house in Omaha, far from Wall Street, is less likely to solve investment riddles today, than fifty years ago.

The first problem of today’s analyst is the sheer volume of information that is freely available over the Internet.

A search for the term “Citicorp” in the SEC files turns up over one thousand documents. The same term on Google, turns up almost one million hits.

Somewhere in this vast sea of information may be the “smoking gun” that either reveals a security as an outstanding opportunity or unacceptable risk.

It is clear that this data should be “mined”, and that the task is greater than any individual can handle alone.

|

|

|

|

Capital Market Wiki --- a work in progress

|

|

|

|

|

The analyst of the 21st century must be ready to engage in collaborative research. The solitary hero-analyst can not handle the job alone, anymore.

The solution to the problem lies in modern knowledge handling technology, including OSINT techniques, crowdsourcing, wiki software, and capital market taxonomy.

Capital Market Wiki is a project that addresses this issue.

I’ve written on this a bit in previous articles:

See: Crowdsourcing investment research: opportunities in OSINT and Free information and the Efficient Market Hypothesis and Crowdsourcing investment research: Capital Market Taxonomy and Innovation in investment research; dealing with free information and Modern technology for institutional investment research and New technology in open source investment intelligence

This topic is extensive.

I’ll have more to say, later.